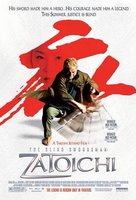

Zatoichi and Meiko Kaji

Zatoichi and Meiko KajiAfter spending the better part of June and July obsessing over the World Cup and watching roughly 130 hours of soccer (and then slowly weaning myself off The Beautiful Game by watching the first two seasons of the cheeky BBC soap opera

Footballers Wives), I decided I had to put away the Sports section and pick up the Fine Arts section. That's why I'm currently on a Movie Vacation. Of course, when it comes to films, I'm a total devotee of Japanese films, in all their wonderful forms, be it the classic post-war

Chambara/Samurai films, Kinji Fukasawa's 1970s post-

Godfather Yakuza film classics, or even the now fashionable post-

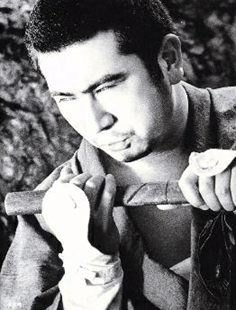

Ringu J-Horror genre. But there are two icons of 60s and 70s Japanese cinema that have always enthralled me and who I've been reassessing this week:

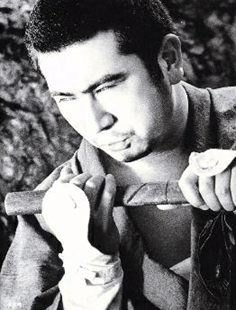

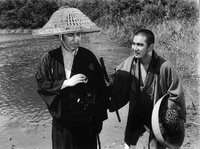

Shintaro Katsu (above left) of the Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman series and

Meiko Kaji (below right), best known as Sasori of the

Female Convict Scorpion women-in-prison (W.I.P.) films series,

who also starred as a recurring character in the 60s

Stray Cat Rock girl gang series and as avenging orphan Yuki in director Toshiya Fujita's two

Lady Snowblood films - the latter the inspiration for Quentin Tarantino's

Kill Bill films (he even used two of Meiko Kaji's songs in his films: the

Lady Snowblood theme "

The Flower of Carnage" in

Kill Bill 1 and "

Urami Bushi (My Grudge Blues)" from the

Female Convict Scorpion series in

Kill Bill 2). Kaji also appeared in three of director Kinji Fukasaku's 70s gangster films, including a memorable turn in

Yakuza Burial - Jasmine Flower (

Yakuza No Hakaba - Kuchinashi No Hana, 1976) as the Korean wife of an imprisoned Yakuza boss who falls in love with a morally ambiguous cop played by Tetsuya Watari.

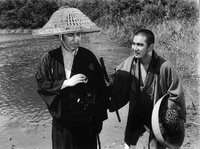

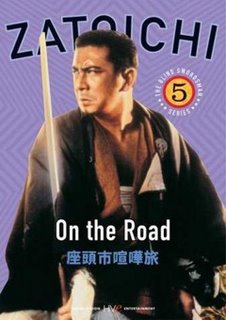

Itchy for IchiThe Charles Theater's samurai film revival series rekindled my obsession with the Zatoichi films. On August 4, I joined my fellow obsessive/sensei

Big Dave Cawley (King of Men) and cohorts Not-So-Big

Dave Wright and punk-pop physicist

Jason Fritsch (erstwhile guitarist in

The Gamma Rays) at the Charles to see

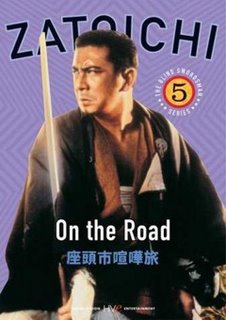

Zatoichi and the Fugitives (1968), followed the next Saturday by perhaps the best in the series,

Zatoichi On the Road (1963). I was so inspired by the latter that I whipped out my credit card to purchase the AnimEgo

Zatoichi DVD box set collection. Kung Fu Cinema's

review astutely compared

On the Road to a mesh of two Akira Kurosawa films with a touch of Shakespearean romantic tragedy:

"Seemingly free from constraints of humility in previous episodes, Ichi has become more confident and more willing to show off his incredible sword skills which is good news for action fans. The story is an adventurous one that could be compared to Akira Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Yojimbo (1961). The first half features Ichi's journey with Mitsu, played by a lovely Shiho Fujimura who returned to the franchise in 1967 for Zatoichi's Cane-Sword. The latter half features Ichi playing both sides in a turf war, much as Toshiro Mifune did in Yojimbo. Both parts are woven together well with Ichi's love for Mitsu being the dominating theme."

The next week, Not-So-Big Dave and Jason dropped out so it was just me and Big Dave and my girlfriend

Amy catching the final Zatoichi screening at the Charles,

New Tale of Zatoichi (1963), which, like

Zatoichi and the Fugitives, was directed by Tokuzo Tanaka. While not the best in the series,

New Tale was significant in fleshing out details about Ichi's shadowy past. In it, he travels to his old village, where he meets his old sensai Banno, the man who taught Ichi his sword skills "four years ago." Ichi also visits his parents' graves and his deaf old granny. More importantly, this is the episode where Ichi has his heart broken when he asks for the hand of Banno's sister, Yayoi, only to be called an impudent blind dog by his incensed teacher. That's because the selfish former samurai wants to marry his sis off to some hotshot samurai in Edo, among other nefarious schemes - like helping the Mito Goblins, a gang of bandits, kidnap one of his pupils to extort money from the kid's rich Daddy-san. Truly, as Big Dave said - in mock-

Simpsons' Comic Store Guy voice - Banno was the "worst sensei

ever!" Yup, Pat Morita in

The Karate Kid he's not!

Zatoichi: Columbo with a CaneThe Zatoichi series, like most all chambara films, are set during the Tokugawa period and star Shinatro Katsu as Zatoichi, literally "Ichi the Masseur," masseurs being a customary line of work for blind men of this period. Masseurs at this time were at the bottom of the social caste and were subject to scorn from everybody, from the lowest peasant to the mightiest samurai. And who is this Ichi? No one writes better about Katsu's "franchise" character than Alain Silver, whose essential tome

The Samurai Film (1977, revised 2005) contains the definitive chapter on Zatoichi and the Blind Swordfighters genre (yes, there was more than one!). Silver writes:

The title character and "hero" of these motion pictures is Zato Ichi, a burly, crew-cut masseur. Dressed in a short , wrinkled kimono of plain grey cloth and walking on straw sandals or sometimes perched unsteadily on forbidden wooden clogs, he picks his way slowly through crowds and across country with the help of a wooden cane, because he is also a blind man. Nevertheless, as two dozen productions have amply proven, he is one of the deadliest swordsmen in chambara film.

That's because Zatoichi has overcome his visual handicap by relying on other senses. He literally fights "by ear," his acute aural abilities often indicated onscreen by a zooming close-up of his ear. Countless films depict him showing off his radar sound capabilities, from cleaving an arrow in half in mid-flight to dissecting a moth with a toothpick while finishing up his dinner.

Unlike the traditional samurai master swordsman, Zatoichi does not present a heroic figure. Rather, he is often bumbling, silly and self-deprecating, always looking to avoid a fight whenever possible. Unless a line is crossed. Like calling him a "blind bastard" or hurting innocent people. As Silver points out, Ichi has a soft spot for the weak, "for widows and orphans, for anyone whom he regards, like himself, as a victim of

shushigaku or feudal class structure or some unspecified quirk of fate."

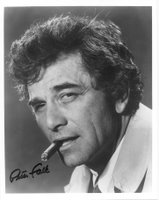

But the happy-go-lucky village idiot image he presents is but facade, much in the way Peter Falk as the disheveled TV detective Columbo would seem to talk aimlessly while walking around in the world's seediest raincoat while all the while slyly taking in his surrounding and trying to break down his opponents. In place of Columbo's raincoat, Zatoichi has a wrinkled kimono. And in place Columbo's cigar, Zatoich subsitutes the blind man's wooden walking cane. But like Columbo, he's a sly one who follows a moral code; just as behind Columbo's cigar is a pair of cuffs ready to collar the caught out criminal, so Zatoichi's cane is a sheath for a sword ready to make mince-meat of his victims and send them to meet their maker.

Zatoichi balances his anger with bouts of self-deprecating humor and the temporary escapes from his plight that vices offer. Asked it he drinks sake, he will laugh and reply, "Heh heh, I would not refuse it." As a card-carrying Yakuza, he also likes to gamble, and, in at least one film (

New Tale) it is implied that he lays down with a prostitute. But his humors are irregular, as Silver notes. "At times he summons up sufficient stoicism to witness injustice or endure a personal wrong silently and inactively, without retaliating." But "when genuinely provoked to anger, when a gambling boss or petty official has betrayed his trust, Zato Ichi can display an indominable ruthlessness of his own."

Yet Ichi is ultimately a tragic hero, seemingly fated to keep on killing despite his aversion to it. His adherence to

butsudo (Buddhism) as Silver points out, means that he is forever repenting his violent life, subjecting himself to endless self-recriminations for the blood on his hands. And, more importantly, he

never gets the girl, even though he's more popular with the ladies than Johnny Depp. More cogent comments on this subject from the folks at Kung Fu Cinema:

It's clear that the real reason Ichi never settles down with one woman is that it would hinder the potential for both dramatic and romantic tension which are key factors to the success of the series. Nevertheless, it is both unrealistic and saddening to see a blind man of low social stature given so many opportunities to find happiness with a woman, only be denied or to deny it himself. Don't let Shakespeare fool you, the truth is that the Japanese are the real masters of tragic romance in pop culture...

In this regard,

Zatoichi On the Road is a prime example of Heartbreak City. As is

New Tale of Zatoichi. Purple words on a gray background, to be a blind masseur and to be turned down - by your sensei. Whom you slay in the final reel - that puts the nix on any matrimonial plans with a sensei's sis!

Despite adhering to formulaic plots and repetitive action sequences, Zatoichi remains the most popular series in Japanese film history. Maybe that's because, like a Bollywood film, you get a little bit of everything in it: action, fighting, romance, tragedy, melodrama, social commentary, comic relief - even musical numbers. (Yes, Zatoichi actually sings in

Zatoichi Meets the One-Armed Swordsman - but with a voice like that, it's no wonder he chose to make a living as a masseur!)

Zatoichi Film Factsheet:Want to watch Zatoichi films on DVD? Shintaro Katsu starred in 26 Zatoichi films between 1962 and 1989. (To see the complete 26-film list, click

here.) He made 25 films in 11 years - from the first, 1962's

The Tale of Zatoichi through 1973's

Zatoichi in Desperation - then took a 16-year sabbatical before coming back for 1989's

Zatoichi. During that time, Katsu transferred the Zatoichi series to the small screen, creating 100 episodes for the Japanese

Zatoichi TV series between 1974 and 1979. DVD distributor Tokyo Shock (a division of

Media Blasters) - who released the DVD of 1989's

Zatoichi - was able to get the rights to the TV series and has begun releasing them on DVD (each of the five TV series DVDs released so far contains three 60-minute episodes). To see a list of TV episodes, click

here.

The 26 films have been divided into offerings from three companies.

Home Vision Entertainment (under its Image Entertainment imprimatur) has the early releases, totalling 18 titles, while AnimEgo has 7, mostly later releases (including the great

Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo starring Toshiro Mifune and Chinese martial arts legend Jimmy Wang Yu in

Zatoichi Meets the One-Armed Swordsman), which it offers in a collector's

box set. Tokyo Stomp owns 1989's

Zatoichi, aka

Zatoichi 26 or

Darkness is His Ally.

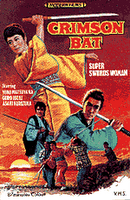

The series also spawned numerous imitators, most notably the short-lived

Crimson Bat films from Shochiku Studios, which featured the very popular actress

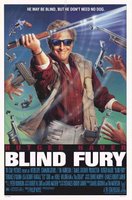

Yoko Matsuyama as the fearless blind swordswoman. In 1989, Rutger Hauer starred as a Zatoichi-inspired character in

Blind Fury (tagline: "He may be blind, but he don't need no dog!"), which was basically an American remake of 1967's

Zatoichi Challenged.

And in 2003, Takeshi Kitano made Zatoichi a blonde in his remake

The Blind Swordsman Zatoichi. Kitano was the only Japanese actor other than Shintaro Katsu to portray Zatoichi. Oddly enough, Kitano, who made his name as a legendary comedian, plays Ichi straight, coming nowhere near the humorous charm of Shintaro Katsu.

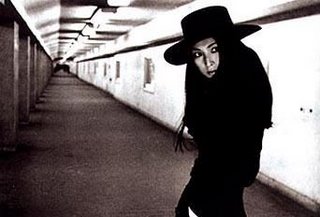

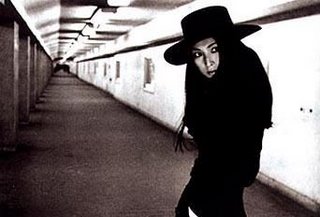

Meiko Kaji: The Eyes Have It

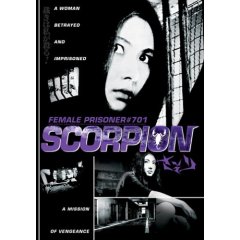

Garbo was called "The Face of the Century." But in world cinema, there is nothing quite like the ice-cold stare (glare?) of Meiko Kaji as Sasori (Scorpion) in the

Female Convict Scorpion film series. Like the obsidian eyes of Jess Franco starlet

Soledad Miranda (

Vampros Lesbos,

She Kills in Ecstacy), Sasori's cryogenic eyes are the iconic stuff of legend. In

Cinema Sewer #18 (the February 2006 "Girls in Prison" issue), Robin Boogie introduces his review of Meiko Kaji's

Female Convict Scorpion films with words that speak directly to my heart:

Maybe it's the film geek in me, but I shore dew luvs me ah dame that fucks shit up in a movie. There is just someting so satisfying about a confident woman who takes no dung. And hands out pain and suffering to anyone who gets all up in her grill and deserves to taste a slice of pummel pie...While not a martial arts or weapons expert, the quiet rage filled character of Sasori (Scorpion) played by the raven haired Kaji in the Female Convict Scorpion movies from the early '70s is possibly the toughest, non-nonsense woman I've ever had the pleasure of seeing immortalised on film...if you cross her...you will undoubtably find your ass either dead or in some excruciating agony.

Robin Boogie's article on Kaji is great, but the best print source I've found is Chris D.'s chapter on her in

Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film (2005). Chris D. (short for Desjardins) - who works as a programmer for LA's non-profit

American Cinematheque - also was lucky enough to get an informative interview with Ms. Kaji in 1997, which is included in his highly recommended book. (By the way, America Cinematique shows some of the best and rarest Japanese cult films in its "Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film" series and is responsible for bringing out DVD releases of such classics as Shunya Ito's

Female Convict Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (Joshuu Sasori: Dai-41 Zakkyo-bô) (1972) and Yasuharu Hasebe's

Black Tight Killers (Ore Ni Sawaru To Abunaize) (1966) - both with excellent liner notes - as well as outstanding films by

Kinji Fukasaku and

Seijun Suzuki. To learn more about Chris D. and the American Cinematique, see American Cinematique's

MySpace Profile.)

Female Convict Scorpion

Meiko Kaji started her film career at Nikkatsu Studios in 1965 under her given name,

Masako Oto. But she only got top billing in one film,

Mini Skirt Lynchers (Zinkoku Onna Rinchi) before changing her name to Meiko Kaji in 1969. And it wasn't until 1972 that she found her breakthrough role as Matsu/Sasori (Scorpion) in Shunyo Ito's

Female Convict Number 701 - Scorpion (

Joshuu Go 701 - Sasori). Adapted from the manga by

Toru Shinohara, it tells the story of an innocent woman whose life is destroyed by her duplicitous boyfriend, a cad cop on the take from the Yakuza who asks her to go undercover for a drug bust. But Matsu instead finds herself gang-raped by the thugs, after which her boyfriend shows up to grab his pay-off money, tossing some tip money on her bloodied, defiled body by way of thanks. It's at this moment that Matsu realizes she should have read

He's Just Not That Into You, and tries to stab him with a knife. Japan doesn't buy into the French "Crime of Passion" defense, so Matsu is thrown into jail, where she fine-hones both her hatred of men and her cutlery skills.

It would be easy to stereotype Meiko Kaji as a "sex kitten with a whip" badass babe in these W.I.P. exploitation films, but that cheapens her accomplishments. In Meiko's hands, Matsu is no one-dimensional character but rather, thanks to her face, thanks to her "grace" - that aura of calculating cool exhibited in her economy of movement (she never acts without a purpose) and speech (why waste words when actions peak louder?) - and thanks to those black-portal-to-the-soul eyes that glare at her oppressors, her Sasori transcends reality to become a mythic and iconic figure. Like a Helen Mirren in

Prime Suspect she exudes class with a tough cookie edge; you think you can take advantage because she's a woman, but tangle with her and you'll soon regret it. Like the guy below regrets it:

And like the tight-lipped Clint Eastwood in his Man With No Name/Spaghetti Western period, Meiko Kaji as Matsu/Sasori minces no words - why bother speaking? - unnerving her opponents with her silence, making her few utterances all the more weighty in significance. She acts when she needs to act, wasting no unnecessary movement. All of which is offset by the stoic beauty of her face.

As Ivan Denisov, reviewing

Female Convict #701 - Scorion for the

Yakuza Eiga website put it:

"How a man can watch this lady’s films without falling in love with her is beyond me. Here we must credit her first for serious reworking of Matsu’s image (film is based on manga series, where Scorpion uses a lot of foul language, which Kaji didn’t want to do, hence we get not a killer with a dirty words, but very taciturn deadly force) and for creating a heroine comparing to whom Clint Eastwood’s characters seem soft-hearted and sentimental chatterboxes. Not to mention that she looks equally radiant in prison rags and stylish black outfit of an avenging angel. Whenever Meiko Kaji is on the screen one can’t take one's eyes off her."

Ah, so true Ivan, so true! Plus, in the first film, there is LOTS of gratuitous nudity, in fact the shower sequence at the start of

Female Convict #701 - Scorpion may be

the most gratuitous use of nudity in a credit sequence ever, as an endless parade of young nubiles giggle their way into the prison shower stalls like runway models. It's the only light moment in the film before the gorefest begins. The first film also offers, to my knowledge, the only nude scene featuring Ms. Kaji, albeit only a fleeting glimpse of her breasts during her rape scene.

And, as Ivan points out, Meiko Kaji had a lot to do with improving the character of Sasori from stock exploitation "avenging angel" to something more thought-provoking. Chris D. agrees, as he writes in his liner notes for American Cinematique's

Female Convict Scorpion - Jailhouse 41 DVD:

"The first four films with Kaji also prove to be a bit of an improvement over their manga (comic book) source. When Kaji balked at the continually spewed obscenities of sasori as she appeared by creator Tooru Shinoharo in Big Comics magazine, she and director Shunya Ito decided to make the character more mysteriously elemental. Sasori is no longer a foul-mouthed ruffian but a virtually silent, deadly force uttering only a few cryptic sentences in each film. Female Convict Scorpion posseses all the traditional exploitation elements but with a surreal, comic book use of color and a succession of mythical/archetypal images leave a haunting, eerie shiver when the last scene unspools."

In other words, the director and actress took what could have been disposable pop cultural trash and made it art. Iconographic art at that. A number of action film series heroes/heroines have a signatire look, and Sasori was no exception. Clint Eastwood's Man With No name had the long duster coat, The Crow had his Goth leather look, and so on. For Sasori, it was the black bolero hat and long black trenchcoat, an all-black, funereal ensemble that at first glance makes me think of John and Yoko's look circa the Beatles'

Hey Jude album. Only Meiko's no Yoko. No peace, love and understanding in her look, baby. No sir-ee.

Meiko Kaji starred in four of the six Scorpion series films produced by Toei Studios, the first three directed by Shunyo Ito and the fourth directed by

Yasuharu Hasebe, who had previously directed her best

Stray Cat Rock series film, 1970's

Stray Cat Rock: Sex Hunter. (By the way, these

Stray Cat Rock films are loads of fun, filled with great mod a go-go soundtracks, especially

Sex Hunter, which features Kaji as a whip-wielding gang leader. Hasebe's other great film frolic is

Black Tight Killers (1966), which is worth tracking down as it's a great party tape, kind of like a

What's Up Tiger Lily? spy thriller without Woody Allen's commentary.)

Meiko Kaji tired of the increasingly formulaic gore approach in the series, letting

Yumi Takagawa take over in 1976's fifth installment

New Female Convict Scorpion, while newcomer

Yoko Natsuki picked up the bloodletting role in 1977's final entry,

Special Cellblock X. Both films were directed by

Yu Kohira.

I've only seen the first two installments of the Scorpion series, of which

Jailhouse 41 is the stronger film, but I highly recommend checking out all of the films starring Ms. Kaji.

Like the Zatoichi franchise, Scorpion also inspired its share of knock-offs. Nikkatsu Studios produced two racy

Female Convict 101 (Joshuu 101) films during 1976-1977 and in 1991

Evil Dead Trap director

Tashiharu Ikeda revived the series with

Female Convict Scorpion - Death Threat (Joshuu Sasori - Satsujin Yakoku). Chris D. says the series continued into the late '90s with

Daisuke Gotoh's

Sasori in the U.S.A. (AKA

Scorpion's Revenge). Unlike the other Scorpion knockoffs, this 1997 entry starring

Yoko Saito (look for her also in Takashi Miike's

Salaryman Kintaro, 1999) as Matsushima/Nami/Sasori/Scorpion is available on DVD (from the producers of the cheesy/sleazy

Zero Woman), but is supposed to be ripe for landfill disposal, according to imdb reviews. Still, a part of me (the imp of the perverse part) wants to see just how bad it is.

The full Scorpion filmography is listed below:

Toei's Female Convict Scorpion series filmography:Female Convict #701 - Scorpion (1972) (Pt. 1)

Female Convict Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (1972) (Pt.2)

Female Convict Scorpion: Beast Stable (aka Beast Room, Department of Beasts) (1973) (Pt. 3)

Female Convict Scorpion: Grudge Song (1973) (Pt. 4)

New Female Convict Scorpion: Prisoner #701 (1976) (Pt.5)

New Female Convict Scorpion: Special Cellblock X (1977) (Pt.6)

Other Scorpion FilmsFemale Convict Scorpion - Death Threat (Joshuu Sasori - Satsujin Yakoku) (1991)

Sasori in the U.S.A. (AKA Sasori's Revenge) (1997)

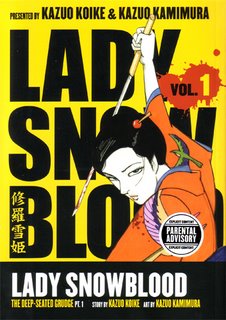

Lady Snowblood

Following the success of the first two installments of the

Female Convict Scorpion films at Toei Studios, Meiko Kaji went to Toho Studios to star as Shura Yuki in

Lady Snowblood (

Shura Yukihime) (1973) - a role that cemented her stature as a cult film siren - and its follow-up,

Lady Snowblood 2 - Love Song of Vengeance (

Shura Yukihime - Urami Koi Uta) (1974). Both films were directed by Toshiyo Fujita and were based on the

manga by

Kazuo Koike, who was also the author of

Kozure Okami, or

Lone Wolf and Cub (which was made into a film series starring Shintaro Katsu's brother

Tomisaburo Wakayama as Ogami Itto; Two Degrees of Separation: Tomisaburo, as a one-armed swordsman, would battle his bro Shintaro in the second Zatoichi movie, 1962's

The Tale of Zatoich Continues (

Zoku Zatoichi Monogatari), and also appear in 1964's

Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold)(

Zatôichi Senryô-Kubi)). The prolific Okami also wrote

Razor Hanzo (which was turned into a 70s film series starring Shintaro Katsu),

Crying Freeman, and

Samurai Executioner.

The manga and films tell the story of Yuki, a daughter born in prison to a convict mother who slept with prison guards and priests so that she could bear a child to avenge her rape and the murder of her husband and son at the hands of a gang of thugs during the Ketsuzel "Blood Tax" Riots of 1873. This was a time of forced conscription when the Japanese government, hoping to catch up with the Western World in terms of military power, sent government officials to every town and village to sign up any boys over the age of 17 for military service. The government agents were rumored to wear white suits; unfortunately, when Yuki's family came to one town where her dad was to start teaching school, her father was dressed in a white suit. The four-member gang convinced the villagers that Yuki's Dad was a government agent and slaughtered him and his son, and raped Yuki's Mom for three days and three nights. One of the gang members who lusted after Yuki's mother, kidnapped her and took her away to another town, where she bided her time until an opportunity to kill him arose. Yuki's mother killed her oppressor, but was sent away to prison for her "crime." She died after giving birth to Yuki in her cell one snowy night, entrusting her care to a cellmate due to get out.

Orphan Yuki was raised by a priest,

Dokai, who taught her martial arts and an "Aunt" - her mother's former prison cellmate

Mikazuki Otoro - who teaches Yuki pickpocketing. The child was conceived and raised to avenge her mother and as such in continually considered inhuman, a creature of purpose rather than flesh and blood and emotion. Or, a creature of Hell. In fact, her full name

Shura Yuki Hime translates literally as Netherworld (

Shura) Snow(

Yuki) Lady (

Hime), I guess so-called because she was born during a snowy night and Snow Hell isn't as cool-sounding as "Snowblood." When she reaches the age of 20, Yuki sets out to kill the three remaning crooks who wronged her family.

Like Matsu/Sasori in the

Female Convict Scorpion series, Yuki is a character who pretty much detests men and, at least in the explicitly kinky manga, is frequently depicted in lesbian encounters.

She's the once wielding the sword, you see.

Of the two films, only the first is essential viewing. The second is pretty weak, despite a great supporting role by

Juzo Itami (famed director of such Japanese comedies as

Tampopo and

A Taxing Woman) as an anarchist writer that Yuki is hired to slay. And very political, which isn't surprising given the time it depicts. The story is set against the transition-into-modernity period in Japanese history known as the Meiji Restoration. Starting in 1867 and ending just before the First World War, this was the post-Tokugawa Shogunate (1600-1867) period when Japan was becoming Westernized; as a result, the film and manga is rife with political references.

It's easy to see why Quentin Tarantino was a fan of

Lady Snowblood. While it's certainly not a bad film, it is not what I would call high art either. Rather, it's a classic exploitation film, full of gratuitous and stylized violence. Arteries don't just spray, they gush. And they gush in bright crimson technicolor red. And the theme song, repeated at the end and referenced in snippets throughout, is pretty cool and, well, like Ivan Denisov said, when Meiko Kaji's on the screen, you just can't take your eyes off of her. She has that kind of presence. A true star. Meiko Kaji is like Shintaru Katsu is that respect: a franchise player.

Zatoichi Links:Zatoichi in Wikipediae-budokai.com review

Images Journal review

The Samurai Film (by Alain Silver)

Zatoichi the Blind Swordsman DVD Box Set (AnimEgo)

Zatoichi Filmography (26 films)

Zatoich TV series (100 episodes)

Zatoichi films on DVD (Amazon.com)

Zatoich TV Series on DVD (Amazon.com)

Meiko Kaji Links:Cinema Sewer #18

Meiko Kaji Links:Cinema Sewer #18 article

Outlaw Masters of Japanese Cinema(by Chris D. - has a Meiko Kaji chapter)

Cult Sirens: Meiko KajiMeiko Kaji in Wikipedia

This disturbing pic is from Grady Hendrix's wonderful Asian Film Blog, Kaiju Shakedown. Though Devil Dick Bike Man appears to be naked, and hence rather vulnerable, at least he's sporting a rather sturdy looking protective helmet. Wonder how he signals for turns?

This disturbing pic is from Grady Hendrix's wonderful Asian Film Blog, Kaiju Shakedown. Though Devil Dick Bike Man appears to be naked, and hence rather vulnerable, at least he's sporting a rather sturdy looking protective helmet. Wonder how he signals for turns?